This is a rudimentary explanation of the of the Squash AI program, if you want more details, contact me via LinkedIn.

Introduction #

What is SquashAI? Why did I make it? And why is it important?

SquashAI is a mobile application intended to help squash players improve their game. It does this by providing a way to track the player’s performance and provide feedback on how to improve. It also stores that information to track progress over time.

I made it because I wanted to improve my own game, and I thought I might as well put my programming skills to use. I also wanted to learn more about machine learning and computer vision, and this was a great way to do that.

As I progressed in the project, I realized that it could be used to help other players improve their game, especially people who don’t don’t come from economic backgrounds that can support paying for coaching fees. This should be way cheaper to run and democratize coaching for the masses. In addition, coaches aren’t statisticians. They can’t tell you how your game has changed over time with the accuracy that a computer can. Also, if all the other sports have stats like RBI (baseball), passing yards (american football), and PPG (basketball) why can’t we? We’re in the Olympics now, we better act like it.

How it works #

There is one point of data collection: the video. Recorded from a single smartphone, a video can either be streamed live into the program, or it can be uploaded from the device’s storage. Once there is a feed, the real work can begin. Three key data points are collected every frame:

- The position of the ball

- The positions of both players

- The bounds of the court

1. Ball Tracking #

We can leverage basic computer vision techniques (KNN background detection, dilation, and more) with OpenCV to get the position of the ball ~90% of the time. This is based off an attempt by Duncan Morris, but I’ve made some changes to make it more robust1. Effectively, the pipeline looks like this: Video -> Preprocessing -> Background Subtraction -> Dilation -> Filtering -> Contour Detection -> Ball Position

Preprocessing: #

- resize the frame to

970 x 540pixels - that’s really it, we want to keep all the information we can

Background Subtraction: #

- Using OpenCV’s

createBackgroundSubtractorKNN()function, we can get a mask of the background. It needs a frame count to use as history to compare the change in each pixel so it acn tell what has changed. A higher history isn’t always better, because camera shake can change more pixels than intended, so ideally it’s actually dynamic. There’s another way we can optimize this too. We know the top possible speed of the ball, so we can limit the area it does the KNN calculations on2.

Dilation: #

After a conversation with Dr. Joe Webber, I now know the way I’m doing it isn’t the best, so I’ll update this when I implement his feedback The KNN-Background Subtraction leaves a lot of noise, so we can use dilation to get rid of it

Filtering: #

working on it, see that Dr. Webber comment above

Contour Detection: #

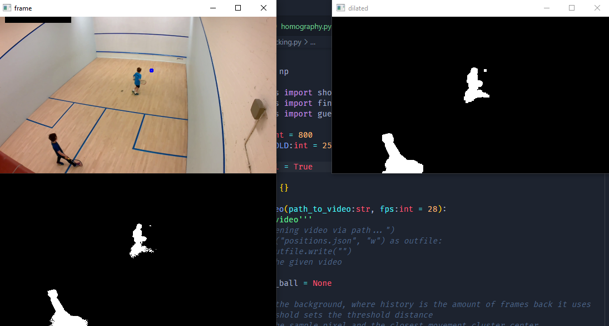

Currently, I’m using shilouette detection to identify what part of our dialated foreground is the ball. Turns out, we can actually use connected-components instead. This requires less math, and is more accurate. Finally, when rendered it looks like this (bottom left: KNN, top right: dialation, top left: contour detection overlayed on original frame):

2. Player Tracking #

Using the Apache 2.0 licensed MoveNet, developed by Google, we can get the following data:

“A float32 tensor of shape [1, 1, 17, 3]. The first two channels of the last dimension represents the yx coordinates (normalized to image frame, i.e. range in [0.0, 1.0]) of the 17 keypoints (in the order of: [nose, left eye, right eye, left ear, right ear, left shoulder, right shoulder, left elbow, right elbow, left wrist, right wrist, left hip, right hip, left knee, right knee, left ankle, right ankle]).” 3 Rendered:

3. Court analysis #

Using openCV’s powerful toolset, we can use functions like getPerspectiveTransform() to unwarp the court as we know the out and service lines are all straight (hopefully, if they aren’t you’re playing on a wack court).

The top speed of the ball ~267 kph (166 mph) according to Guinness World Records ↩︎

From Google’s Writeup ↩︎